A Skeptic Considers His Jewish Origins

Some years ago, while reading the second book of the Jewish Bible, Exodus, I came across the words, “Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who knew not Joseph.” At that time, I was interested in the story of the Egyptian pharaoh, Akhenaten, his religious revolution, and his founding of a new capital, Amarna on the Nile. I had learned that, soon after his early death, the previously displaced priesthood obliterated all traces of his capital and his revolution.

The question then arose: “What happened to the priests and people of Amarna?” This note is my conjectural response to that question. It is not intended as a scholarly article…no references or attributions are included…but I have made a sincere effort to present a factual background to the premise I present. Several of the underlying historical bases are given below:

Hammurabi (1810 – 1750 BC): was the first king of the Babylonian Empire, extending Babylon’s control over Mesopotamia by winning a series of wars against neighboring kingdoms. Hammurabi is known for the set of laws called Hammurabi’s Code, one of the first written codes of law in recorded history. These laws were placed in a public place so that all could see. The code contained 282 laws, written on 12 tablets. The structure of the code is very specific, with each offense receiving a specified punishment.

The punishments tended to be harsh by modern standards, with many offenses resulting in death, disfigurement, or the use of the “Eye for eye, tooth for tooth” philosophy. Putting the laws into writing was important in itself because it suggested that the laws were immutable and above the power of any earthly king to change. The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence. However, there is no provision for extenuating circumstances to alter the prescribed punishment.

Pharaoh Akhenaten (1350 – 1334 BC): (also known as Amenhotep IV) founded a new religion dedicated to the worship of the Aten (the “sun god”). To establish his new faith, he abandoned Thebes, (the old capital), and built a new capital, Amarna, about 190 miles south of Cairo.

Before Akhenaten, the placing of one god in a privileged position never threatened the existence of the remaining gods. The one and the many had been treated as complementary throughout Egyptian history and gods were not mutually exclusive. The Aten, however, was made the only god. The transformation became visibly apparent because of the unparalleled persecution of traditional gods, above all, Amun.* Akhenaten stonemasons swarmed the country and even abroad to remove the name of Amun from all accessible monuments, including even the tips of obelisks, under the gilding on columns and in the letters of the achieves (In fact, Egyptologists use these erasures and later restorations of the name of Amun in order to date monuments to the period before Amarna).

Though Amun felt the worst of the Akhenaten revolution, other gods were also eliminated. He also fought bitterly against the powerful priests who attempted to maintain the worship of the old gods. A new religious literature also arose. This blossoming of culture, however, did not continue after Akhenaten’s death. His son-in-law, Tutankhamen, abandoned Amarna, moved the capital back to Thebes and restored the old polytheistic religion. In the third year of Tutankhamun’s reign (1331 BC), when he was still a boy at the age eleven and probably under the influence of two older advisors (Akhenaten’s vizier Ay and perhaps Nefertiti), the ban on the old pantheon of deities and their temples was lifted, the traditional privileges were restored to their priesthoods, and the capital was moved back to Thebes.

Amarna Letters (14th century BC): written to Egyptian pharaohs in a time of unrest in Canaan, are an archive of correspondence on clay tablets, mostly diplomatic, between the Egyptian administration and its representatives in Canaan and Amurru in the New Kingdom. Abdi-Hiba, governor of Jerusalem, wrote numerous letters to the pharaoh beseeching Egyptian aid against the encroaching Habiru, if the country [i.e., Canaan] were to be saved for Egypt:

“The Habiru plunder all lands of the king.

If archers are here

this year, then the lands of the king,

the Lord, will remain; but if the archers are not here,

then the lands of the king, my lord, are lost”.

When the Tell el-Amarna archives were translated, some scholars eagerly equated these Habiru with the Biblical Hebrews. Besides the similarity of their spellings, the description of the Habiru attacking cities in Canaan seemed to fit, loosely, the Biblical account of the conquest of that land by Hebrews under Joshua or even by names with David’s Hebrew rally against Saul. However, other scholars assert that the Hebrews were actually spelt as IBRI in Egyptian, however the fact that the Egyptian script was a consonant-only script makes this conjecture unlikely.

Scholarly opinion remains divided on this issue. Some scholars still think that the Habiru were a component of the later peoples who inhabited the kingdoms ruled by Saul, David, Solomon and their successors in Judah and Israel. There have also been theories relating the Habiru to the Biblical personages of Eber and Abraham. While some scholars agree that the genealogies traced from Abraham are based on cultural beliefs and are without historical foundation, there are some who feel that perhaps Eber represents an etymological link to the Habiru.

The Babylonian Exile: In 586 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II captured Jerusalem, destroyed its Temple, and deported its leaders and most of its population to Babylon. At the time, the Babylonian Empire was the most powerful state in the ancient world stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea. They had a system of gods, each with a main temple in each of its cities. The chief gods were Anu, god of heaven; Enlil, god of the air; and Enki or Ea, god of the sea. Others were Shamash, the sungod; Sin, the moon-god; Ishtar, goddess of love and war; and Adad, the storm-god.

Babylonian literature was mainly dominated by mythology and legends. Among these was a creation myth written to glorify their god Marduk. According to this myth, Marduk created heaven and earth from the corpse of the goddess Tiamat. Another work was the Gilgamesh Epic, a flood story written about 2000 BC. Scientific literature of the Babylonians included treatises on astronomy, mathematics, medicine, chemistry, botany, and nature. And, as noted above, the Empire was governed by a set of laws: The Hammurabi Code. This period saw the emergence of scribes and sages in the Jewish leadership and the addition of prophetic books of the Bible. The period also saw the emergence of the central role of the Torah in the life of the Jews.

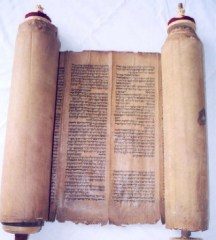

The Torah: There is evidence that the Pentateuch [five books of Moses] was written over the course of several centuries (900 -500 BC) and that the final version, including the prophets and psalms, came into existence some time after the Exile. The Torah’s account of the Exodus, therefore, was of biblical events that had transpired many centuries earlier and had been transmitted orally from one generation to the next.

My Premise

There is evidence that, with the early demise of Akhenaten (however it may have happened), the old priesthood and succeeding Pharaohs made every effort to eradicate all traces of Amarna and of Akhenaten. What then, might we imagine would have happened to the Amarna priesthood and it’s followers? My premise is that, pursued by its enemies, it may have been enslaved, but eventually fled north, entered the land of Canaan [now Israel], warred with and intermarried with the indigenous people, and founded the early Hebrew religion…a religion based on principles derived from Amarna [monotheism and circumcision] and intermixed with the myths and legends of Mesopotamia. It is worth noting that the time period and ancient references to the “Habirus” is not inconsistent with the exodus of the ancient Hebrews.

The Amarna “exodus” would not likely have brought a set of written laws to their new land; there is no evidence of a set of laws applying to the Egyptians in the Amarna period …after all, the pharaohs were considered “gods”…their decrees were law. But, as noted above, there was a set of laws (Hammurabi’s Code) applying to Canaan as part of the Babylonian empire.

When Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem in 598 BC, destroying both the city and the Temple, he deported most of its leaders and a sizable portion of the Jewish population to Babylon. Some biblical scholars believe it was during this exile, that the first books of the Torah (Bible) were written and some agree that the final version was completed during that time. Thus it is possible that the Hebrew scribes melded ancient Babylonian beliefs and laws with the oral history of the Exodus to create the Torah.

A final note: There is no evidence that the indigenous people of Canaan practiced monotheism and/or circumcision; in contrast, there is evidence that Akenhanen and his followers did. This would seem to support the premise. The optional case is…that God told Abraham [Genesis 17] “You shall be circumcised through the flesh of your foreskin…this shall be the mark of the covenant between me and you”… and [Deuteronomy 5] that “Thou shall have no other gods before me.”

Relevant Reading

Moses and Monotheism By Sigmund It was first published in 1939. In it, Freud argues that Moses was actually an Ancient Egyptian and in some way related to Akhenaten, an ancient Egyptian monotheist. The book was written in three parts and was a departure from the rest of Freud’s work on psychoanalytic theory. The book does contain discussion of Freud’s psychoanalytic thinking but was intended as a work of history.

In Moses and Monotheism, Freud contradicts the Biblical story of Moses with his own retelling of events claiming that Moses only led his close followers into freedom and that they subsequently killed Moses in rebellion either to his strong faith or to circumcision. Freud explains that years after the murder of Moses, the rebels formed a religion which promoted Moses as the Saviour of the Israelites. Freud said that the guilt from the murder of Moses is inherited through the generations; this guilt then drives the Jews to religion to make them feel better. Most historians since the 1960’s reject the legitimacy of Psychohistory including Freud’s theories.

Joseph and His Brothers By Thomas Mann

Published over the course of 16 years, Mann’s work retells the familiar stories of Genesis, from Jacob to Joseph (chapters 27-50). Mann considered it his greatest work. Abraham is repeatedly presented as the man who “discovered God” (a Hanif, or discoverer of monotheism). Jacob as Abraham’s heir is charged with further elaborating this discovery. Joseph is surprised to find Akhenaten on the same path (although Akhenaten is not the “right person” for the path), and Joseph’s success with the pharaoh is largely due to the latter’s sympathy for “Abrahamic” theology.

Such a connection of (proto-)Judaism and Atenism had been suggested before Mann, and notably just before Mann began work on the tetralogy’s forth part by Sigmund Freud in his Moses and Monotheism (1939), although here Akhenaten is postulated as a contemporary of Moses (whereas the usual postulate concerning the contemporary pharaoh of Moses, also adopted by Thomas Mann in his novella Das Gesetz (1944), is Ramesses II).

A Radical Approach to Jewish History By Al Mellman

This book offers a unique quadratic theory for learning about our past 4,000 years of Jewish life, including original theories exploding myths and shattering dated hypotheses.